ME: Write a story about how Robert’s Rules govern hiring decisions in a university.

CoPilot:

In the grand, wood-paneled meeting room of Crestwood University, the faculty gathered for a pivotal vote. The atmosphere was tense, as the decision at hand was both significant and controversial: whether to hire Dr. Marcus Johnson, a highly qualified candidate of color, for a prestigious faculty position.

Dr. Evelyn Harper, the dean, called the meeting to order. "Good afternoon, everyone. Today, we will vote on the hiring of Dr. Marcus Johnson for the position of Professor of History. His credentials are exemplary, and he brings a wealth of experience and a unique perspective to our university."

The room was divided. Some faculty members, like Dr. Patel from the sciences and Professor Jameson from the history department, were strong advocates for Dr. Johnson's hiring. They believed his addition would enrich the academic environment and promote diversity.

However, others were resistant. Professor Smith, an influential member of the faculty, voiced his concerns. "While Dr. Johnson's qualifications are impressive, I believe we should consider other candidates who may be a better fit for our department's current needs."

The debate grew heated, with arguments flying back and forth. Dr. Harper tried to maintain order, frequently referencing Robert's Rules of Order to ensure the discussion remained structured and fair.

Finally, it was time to vote. The faculty members cast their ballots, and the results were tallied. When Dr. Harper announced the outcome, the room fell silent. "The motion to hire Dr. Marcus Johnson has not passed."

A murmur of disbelief spread through the room. Dr. Patel stood up, visibly shaken. "This is a grave mistake. We had the opportunity to bring in a brilliant scholar who would have made a significant impact on our university."

Professor Jameson added, "This decision goes against our commitment to diversity and inclusion. We are missing out on a chance to broaden our perspectives and better serve our students."

As the frustration mounted, Dr. Harper tried to calm the room. "I understand this is a deeply emotional issue, but we must respect the decision of the majority."

At that moment, Professor Williams, a passionate advocate for diversity, could no longer contain his anger. He stood up, grabbed a copy of Robert's Rules of Order from the table, and tore it in half. "This is not just about rules and procedures! This is about justice and equality! We are failing our students and our community by not hiring Dr. Johnson."

The room was stunned into silence. Dr. Harper, though shocked by the outburst, maintained her composure. "Professor Williams, I understand your frustration, but we must find a way to move forward constructively."

Professor Williams, breathing heavily, looked around the room. "We need to do better. We need to stand up for what is right, not just follow rules blindly."

Dr. Harper nodded. "I agree that we must strive for a more inclusive and equitable environment. Let's take this as a wake-up call. We will revisit our hiring practices and ensure that we are truly living up to our values."

The meeting ended on a somber note, but with a renewed sense of purpose. The faculty realized that change was necessary, and that they needed to work together to create a more inclusive and just university. Professor Williams' dramatic gesture had highlighted the urgency of the issue, and it sparked a commitment to making meaningful improvements in their approach to diversity and inclusion.

ME: All very nice. But what about the rules of government?

CoPilot:

In the grand halls of the Parliament of Eldoria, the air was thick with anticipation. The nation was facing a critical decision, and the members of Parliament were gathered to debate and vote on a new bill that promised to bring significant changes to the country's healthcare system. However, what should have been a straightforward process quickly turned into a labyrinthine ordeal, highlighting the impossible entanglements of parliamentary procedure.

The bill, known as the Universal Healthcare Act, was introduced by Senator Amelia Hart, a passionate advocate for healthcare reform. She believed that the bill would provide much-needed access to medical services for all citizens, regardless of their income. The proposal had garnered widespread public support, but within the walls of Parliament, it faced a daunting challenge: the forest of rules that governed parliamentary procedure.

As the debate began, Senator Hart took the floor to present her case. She spoke eloquently about the benefits of the bill, but her speech was soon interrupted by a procedural objection from Senator Marcus Reed, a seasoned politician known for his mastery of parliamentary rules.

"Point of order!" Senator Reed declared. "The honorable senator has exceeded her allotted time for opening remarks."

The Speaker of the House, a stern figure with a gavel in hand, nodded in agreement. "The senator's time has expired. We will now hear from the opposition."

Senator Hart stepped down, frustrated but undeterred. She knew that navigating the procedural rules was part of the game, but she hadn't anticipated just how complex and restrictive they could be.

As the debate continued, various senators proposed amendments to the bill. Each amendment required a separate vote, and each vote was subject to its own set of procedural rules. Some amendments were ruled out of order due to technicalities, while others were delayed by lengthy discussions on procedural points.

Senator Reed, a master of parliamentary tactics, used every rule in the book to slow down the process. He called for quorum checks, demanded roll-call votes, and raised points of order at every turn. The proceedings became a tangled web of motions, counter-motions, and procedural maneuvers.

In a final bid to block the bill, Senator Reed launched a filibuster. He took the floor and began a marathon speech, using every minute of his allotted time and then some. The rules allowed him to speak as long as he remained standing and did not yield the floor.

Senator Hart watched in dismay as the hours dragged on. The filibuster seemed unbreakable, and the bill's supporters grew weary. The forest of rules had become an impenetrable thicket, preventing any progress.

Just when it seemed that all hope was lost, a young parliamentarian named Alex Turner stepped forward. Alex was new to the political scene but had a keen understanding of parliamentary procedure. He approached Senator Hart with a plan. He held up a dog-eared copy of Robert’s Rules.

"There's a little-known rule that allows for a motion to end debate if a supermajority agrees," Alex explained. "It's rarely used, but it might be our only chance."

Senator Hart nodded, willing to try anything. She rallied her supporters and called for the motion. The Speaker, surprised by the unexpected move, called for a vote. To everyone's astonishment, the motion passed with the required supermajority.

The filibuster was ended, and the debate resumed. With renewed energy, Senator Hart and her allies pushed forward. Despite further procedural hurdles, they managed to bring the bill to a final vote.

In the end, the Universal Healthcare Act passed by a narrow margin. The victory was hard-won, and the process had highlighted the need for reform in the parliamentary rules themselves. The experience had shown that while rules were necessary to maintain order, they could also become obstacles to progress.

Senator Hart and her colleagues vowed to work on simplifying the procedural rules, making them more transparent and less prone to manipulation. The story of the bill's passage became a testament to the resilience and determination of those who believed in the cause, and a reminder that even the most impenetrable forests could be navigated with the right knowledge and perseverance.

CoPilot:

I hope you enjoyed the story! If you have any other ideas or need further assistance, feel free to let me know.

Me: I find this hard to believe. If only the world were really like this. But after all, this is fiction. Write another story that highlights how old laws get in the way of justice and how Robert’s rules saved the day.. Please do it again and make the story believable.

TheCoPilot:

In the ancient city of Lexoria, the Council of Elders governed with wisdom and authority. Over the centuries, countless laws had been passed to address the needs and challenges of the times. However, as the city evolved, many of these laws became outdated, creating a complex web of regulations that burdened the citizens.

A young and ambitious leader named Marcus was elected to the Council of Elders. He was determined to modernize Lexoria and believed that simplifying the legal code was essential for progress. Marcus quickly realized that while passing new laws was relatively straightforward, rescinding old ones was a daunting task.

Marcus began his mission by reviewing the city's legal archives. He discovered laws that were centuries old, some of which were no longer relevant or even contradictory to newer regulations. There were laws governing the use of horse-drawn carriages, despite the fact that Lexoria had transitioned to automobiles decades ago. There were also obscure laws about trade practices that hindered modern commerce.

Determined to make a change, Marcus proposed a bill to rescind several outdated laws. He presented his case to the Council, highlighting the need for a streamlined legal system that reflected the current realities of Lexoria.

To Marcus's surprise, his proposal was met with significant resistance. Many of the older council members were reluctant to change the status quo. They argued that the old laws were part of Lexoria's heritage and that removing them could lead to unforeseen consequences.

"These laws have stood the test of time," said Elder Helena, a respected member of the Council. "They are the foundation of our society. Rescinding them could create chaos and uncertainty."

Marcus understood their concerns but remained steadfast. He knew that clinging to outdated laws was holding Lexoria back. He decided to take a different approach.

Marcus began by engaging with the citizens of Lexoria. He organized town hall meetings and listened to their frustrations and suggestions. He found that many people were supportive of his efforts to simplify the legal code. Armed with this public support, Marcus returned to the Council with a revised proposal.

He suggested a phased approach to rescinding old laws. Instead of removing them all at once, the Council would review and repeal laws in stages, ensuring that any potential issues could be addressed promptly. He also proposed creating a committee to oversee the process, composed of both council members and citizens.

The Council was more receptive to Marcus's revised proposal. The idea of a phased approach and citizen involvement alleviated some of their fears. After much debate, the Council agreed to form the committee and begin the process of reviewing and rescinding outdated laws.

The committee worked diligently, identifying laws that were no longer relevant and proposing their repeal. The process was slow and meticulous, but progress was made. Over time, the legal code of Lexoria became more streamlined and reflective of the city's current needs.

Marcus's efforts to modernize Lexoria's legal system left a lasting impact. The city became more efficient and adaptable, able to respond to new challenges and opportunities. The story of Marcus and the Council of Elders became a testament to the importance of balancing tradition with progress.

The experience also highlighted the difficulty of rescinding old laws, even when they were no longer relevant. It showed that while passing new laws might be easy, undoing the past required patience, persistence, and a willingness to engage with the community.

In the end, Lexoria thrived, not because it clung to outdated regulations, but because it embraced change while respecting its heritage. The story served as a reminder that true progress often involves navigating the complexities of the past to build a better future.

CoPilot:

I hope you enjoyed the story! If you have any other ideas or need further assistance, feel free to let me know.

Me: All very nice. But what about the victims of old laws? Can Robert’s Rules save them?

CoPilot:

In the ancient city of Lexoria, the Council of Elders governed with wisdom and authority. Over the centuries, countless laws had been passed to address the needs and challenges of the times. However, as the city evolved, many of these laws became outdated, creating a complex web of regulations that burdened the citizens.

A young and ambitious leader named Marcus was elected to the Council of Elders. He was determined to modernize Lexoria and believed that simplifying the legal code was essential for progress. Marcus quickly realized that while passing new laws was relatively straightforward, rescinding old ones was a daunting task.

Marcus began his mission by reviewing the city's legal archives. He discovered laws that were centuries old, some of which were no longer relevant or even contradictory to newer regulations. There were laws governing the use of horse-drawn carriages, despite the fact that Lexoria had transitioned to automobiles decades ago. There were also obscure laws about trade practices that hindered modern commerce.

Determined to make a change, Marcus proposed a bill to rescind several outdated laws. He presented his case to the Council, highlighting the need for a streamlined legal system that reflected the current realities of Lexoria.

To Marcus's surprise, his proposal was met with significant resistance. Many of the older council members were reluctant to change the status quo. They argued that the old laws were part of Lexoria's heritage and that removing them could lead to unforeseen consequences.

"These laws have stood the test of time," said Elder Helena, a respected member of the Council. "They are the foundation of our society. Rescinding them could create chaos and uncertainty."

Marcus understood their concerns but remained steadfast. He knew that clinging to outdated laws was holding Lexoria back. He decided to take a different approach.

Marcus began by engaging with the citizens of Lexoria. He organized town hall meetings and listened to their frustrations and suggestions. He found that many people were supportive of his efforts to simplify the legal code. Armed with this public support, Marcus returned to the Council with a revised proposal.

He suggested a phased approach to rescinding old laws. Instead of removing them all at once, the Council would review and repeal laws in stages, ensuring that any potential issues could be addressed promptly. He also proposed creating a committee to oversee the process, composed of both council members and citizens.

The Council was more receptive to Marcus's revised proposal. The idea of a phased approach and citizen involvement alleviated some of their fears. After much debate, the Council agreed to form the committee and begin the process of reviewing and rescinding outdated laws.

The committee worked diligently, identifying laws that were no longer relevant and proposing their repeal. The process was slow and meticulous, but progress was made. Over time, the legal code of Lexoria became more streamlined and reflective of the city's current needs.

Marcus's efforts to modernize Lexoria's legal system left a lasting impact. The city became more efficient and adaptable, able to respond to new challenges and opportunities. The story of Marcus and the Council of Elders became a testament to the importance of balancing tradition with progress.

However, amidst the efforts to modernize Lexoria's legal system, a tragic case came to light. Elias, a humble farmer, had been languishing in prison for many years due to an old law that forbade the collection of rainwater. This law, passed centuries ago to protect the interests of powerful landowners, had long since lost its relevance. Yet, it remained on the books, and Elias had been caught in its web.

Years earlier, during a severe drought, Elias had built a simple system to collect rainwater to irrigate his crops and provide for his family. Unaware of the ancient law, he was arrested and sentenced to a lengthy prison term. His family struggled without him, and his plight was largely forgotten by the outside world.

As Marcus and the committee reviewed the outdated laws, they stumbled upon the case of Elias. Shocked by the injustice, Marcus immediately brought it to the attention of the Council. He argued that Elias's imprisonment was a clear example of the harm caused by clinging to obsolete regulations.

"Elias is a victim of our failure to adapt," Marcus declared. "We must act swiftly to right this wrong and ensure that no one else suffers the same fate."

The Council, moved by Marcus's impassioned plea, agreed to expedite the repeal of the rainwater collection law. They also ordered an immediate review of Elias's case. Within days, the law was rescinded, and Elias was released from prison.

The day of his release was filled with mixed emotions. Elias was overjoyed to be reunited with his family, but he also felt a deep sense of loss for the years he had spent behind bars. The community rallied around him, offering support and assistance as he rebuilt his life.

Elias's case became a powerful symbol of the need for legal reform in Lexoria. It highlighted the human cost of outdated laws and the importance of vigilance in maintaining a just legal system. Marcus and the committee redoubled their efforts, determined to prevent such injustices in the future.

The story of Elias also sparked a broader conversation about the role of laws in society. Citizens began to engage more actively in the legislative process, advocating for transparency and accountability. The Council, inspired by this newfound civic engagement, committed to regular reviews of the legal code to ensure it remained relevant and fair.

Elias's story left a lasting impact on Lexoria. It served as a reminder that laws, while necessary for order and justice, must evolve with the times. The experience reinforced the importance of compassion and empathy in governance, ensuring that the legal system served the people rather than trapping them in its complexities.

Marcus's leadership and the community's support transformed Lexoria into a model of progressive governance. The city thrived, not because it clung to outdated regulations, but because it embraced change while respecting its heritage. The story of Elias and Marcus became a testament to the power of resilience, justice, and the enduring quest for a better future.

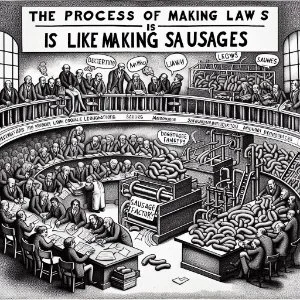

Me: Again, all very nice. But could Robert’s Rules have saved the day and the disaster that descended on Elias? Fed up with CoPilot I put this question to ChatGPT. I uploaded the stories and asked: “review the stories attached and write a story about Robert's Rules that is more realistic and less goody-goody.”

ChatGPT:

Below is a “new, deliberately less idealized story”, written after reviewing the attached material and its tone and themes . I have avoided moral pageantry, heroic gestures, and neat resolutions. The emphasis is on how “Robert’s Rules function in practice”: imperfectly, strategically, sometimes cynically—but still capable of producing limited justice when people know how to use them.

The meeting was supposed to last an hour. It had already gone two and no one had mentioned the agenda since item three. The County Housing Authority met in a windowless room above the courthouse, a place that smelled faintly of dust and burnt coffee. The chairs were bolted to the floor. The rules were laminated and stacked in front of the chair, untouched except when someone needed to stall.

At issue was a set of eviction appeals tied to an ordinance passed in 1974, back when the county still pretended it was rural. The ordinance allowed summary eviction for “nonconforming occupancy,” a phrase no one bothered to define anymore. It had been enforced sporadically for decades, mostly against people without lawyers.

One of them was Maria Alvarez. She sat in the back row, coat folded over her knees, listening to officials speak about her apartment as if it were a filing error. Her attorney wasn’t there; legal aid had sent a letter instead. The staff recommendation was brief: uphold the eviction, cite precedent, move on.

No one mentioned that Maria had lived there eighteen years.

The chair cleared his throat. “We’ll proceed as recommended unless there’s objection.”

There was always supposed to be an objection. Usually there wasn’t.

This time, there was.

“I object,” said Daniel Kruger, a junior board member who had been on the Authority less than a year. He didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t make a speech. He simply said the words and waited.

The chair frowned. “On what grounds?”

Kruger glanced down at his notes. “The recommendation wasn’t circulated within the required time frame. Under our adopted rules, that means it can’t be voted on today.”

There was an immediate irritation in the room—the kind that comes when procedure interrupts momentum. One of the senior members rolled her eyes.

“That’s technical,” she said. “We’ve always handled these administratively.”

Kruger nodded. “That may be true. But we adopted Robert’s Rules by resolution in 1996. They still apply.”

The chair sighed and reached for the laminated copy. He flipped pages, slower than necessary. Everyone knew what was happening: delay, irritation, and the hope that the objection would collapse under pressure.

It didn’t. The chair ruled that the objection was well taken.

“Fine,” he said. “We’ll table the item.”

“Point of order,” said Kruger again. “Tabling requires a motion and a majority vote.”

This time, the irritation sharpened. A motion was made. It passed narrowly.

Maria did not smile. She didn’t know yet what any of this meant.

Two weeks later, the item came back. This time, Kruger came prepared. He didn’t argue that the ordinance was unjust in the abstract. He didn’t accuse anyone of discrimination. He did something more dangerous: he forced the board to follow its own process. He moved to amend the recommendation, inserting a requirement that enforcement actions under the 1974 ordinance be suspended pending legal review.

Someone objected. Debate followed. It wasn’t lofty. It was procedural, narrow, and dull. But it was on the record.

A member tried to end debate early. Kruger cited the rules again. Another member tried to bundle the amendment with unrelated items. Out of order. The meeting dragged. People checked their phones. The chair lost patience.

Finally, the vote was taken. The amendment passed—barely.

Maria’s eviction was stayed. Not overturned. Not declared unjust. Just delayed, pending review.

She still didn’t smile.

Six months later, the county quietly repealed the ordinance. Not because of Maria. Because it was indefensible, legally vulnerable, and now documented as such in the minutes.

No apology was issued. No statement was made. The Authority updated its website and moved on.

Maria stayed in her apartment.

Kruger did not become a hero. He wasn’t reappointed the following year. He had been “difficult,” someone said. “Too procedural.”

But the rules were still there. Laminated. Waiting. And the next time someone said, “Unless there’s objection,” someone else knew what to say.

ChatGTP continued:

If you would like, I can:

Rewrite this in a specific real-world setting, such as a city council, university senate, nonprofit board, or legislature.

Make it darker, showing partial failure rather than success.

Convert it into a parable-style short piece, suitable for inclusion in a book or essay collection on governance and procedure.

Align it explicitly with actual provisions of Robert’s Rules (motions to reconsider, appeal of the chair, suspension of the rules, etc.).

Just tell me the direction

Me: Nothing more to add here, except to note that the version ChatGTP is the paid version, so is probably a step above the university version of CoPilot.