By Kristen M. Budd, Rachel Didner-Jollie

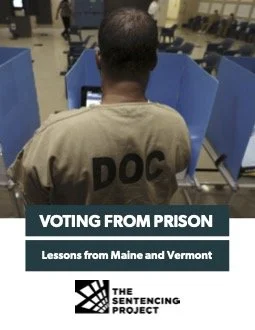

Only two U.S. states – Maine and Vermont – do not disrupt the voting rights of their citizens who are completing a felony-level prison sentence.1 Incarcerated Mainers and Vermonters retain their right to cast absentee ballots in elections. Because of the states’ unique place in the voting rights landscape, The Sentencing Project examined how their Departments of Corrections facilitate voting. We sought to determine experiences and lessons to share nationally as momentum builds in states, such as Illinois, Maryland, and Oregon, to expand voting rights to people completing a felony-level sentence in prison or jail.2

Voting is one prosocial way to maintain a connection to the community, which is particularly important during incarceration, and it helps to build a positive identity as a community member.3 The right to vote is also an internationally recognized human right.4 While voting is a cornerstone of American democracy, an estimated 1 million citizens cannot vote because they are completing a felony-level sentence in prison.5 Given racial disparities in incarceration, people of color are disproportionately blocked from the ballot box due to voting bans for people with a felony-level conviction.6

This first-of-its-kind research is a culmination of a multi-year inquiry in Maine and Vermont about how voting rights are implemented in prisons. The Sentencing Project sought to answer two interrelated questions:

What are incarcerated residents’ views about voting and the voting process?

What are the facilitators and barriers to implementing voting rights within the Department of Corrections, according to Department of Corrections staff and other stakeholders?7

Past research has found low voter turnout among people incarcerated in these states, despite incarcerated residents retaining their voting rights while completing a felony-level sentence.8 This suggests that, in practice, the absentee ballot voting process may be more complex in correctional settings.9

Our findings are based on 21 interviews with staff from the Maine and Vermont Departments of Corrections and other stakeholders who collaborated with these agencies in voting rights work, as well as our survey of incarcerated Mainers and Vermonters in which 132 incarcerated people participated. This investigation revealed:

Nearly three quarters (73%) of incarcerated survey respondents said that voting during incarceration is important to them.

Almost half (49%) of incarcerated respondents said that they did not know how to vote at their facility.

Facilitators that supported voting within the Departments of Corrections included:

Involvement of the Secretary of State’s Office, non-profit groups, and individual volunteers.

Cooperation from the Departments of Corrections’ administration and staff.

Coordination of in-person voter registration drives to assist incarcerated residents with the voter registration process.

Barriers that hindered voting within the Departments of Corrections included:

Incarcerated residents’ lack of knowledge about their voting rights and how to navigate the multiple-step process to vote absentee.

Limited information about candidates to inform voters and a lack of guidance on voting dates and deadlines.

A lack of staff training on incarcerated residents’ voting rights and how to assist incarcerated residents with voting.

Additional logistical challenges included:

Limited access to the paperwork needed to vote (e.g., registration forms, ballot requests).

Delays caused by prison mail and mail external to the facility.

A lack of person-power or capacity by corrections staff and other stakeholders to conduct voting rights work across all facilities.

Based on these findings, The Sentencing Project recommends providing more equitable access to voting and democracy during imprisonment by:

Establishing on-site polling locations in all correctional facilities that have eligible voters.

Expanding education for incarcerated residents about their voting rights and how to vote using an absentee ballot method.

Training corrections staff on incarcerated residents’ voting rights and on the process of assisting residents who are voting from prison.

Increasing access to candidates and candidate information, including hosting candidate forums within the prison.

Permitting and providing access to official government websites as additional avenues to register to vote, request ballots, track ballots, and learn about state and local ballot initiatives.

Such a vision for voting in prisons is attainable. A movement is already underway to increase access to the ballot in jails.10 Due to the fluidity of jail populations – where an average stay is 32 days – coordinating voting efforts in jails can be even more complex.11 Yet, even with such hurdles, turnout in jails with on-site polling locations has surpassed citywide turnout rates in places like Cook County, Illinois and Washington, DC.12 The successful implementation of jail-based voting demonstrates that prison-based voting is possible. Every eligible American citizen should be able to cast a ballot in elections regardless of conviction or incarceration status. In the words of one incarcerated resident in Maine, “I believe strongly [that] voting is a fundamental right for every American citizen. Being incarcerated does not mean you forfeit that right so I voted in here and will most definitely vote out of here.”

Washington, DC: The Sentencing Project, 2025. 36p.