By The Death Penalty Information Center

In 1993, the House Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights conducted hearings on what was then a relatively unknown question: How significant was the risk that innocent people were being wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death in the United States. After taking testimony from four exonerees who had been wrongfully condemned to death row, Representative Don Edwards, the subcommittee chairman, asked the Death Penalty Information Center to research the issue and compile information on how frequently these miscarriages of justice were occurring and what were the reasons why. DPIC began looking more closely into death-row exonerations in the U.S. in the twenty years since the Supreme Court ruled in Furman v. Georgia in 1972 that the death penalty as then administered was unconstitutionally arbitrary and capricious. That research—undertaken before the availability of the internet—uncovered 48 cases in which a wrongfully convicted person had been released from death row because of innocence. The results of DPIC’s research were released in a Staff Report by the Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights Committee on the Judiciary, One Hundred Third Congress, First Session, Innocence and the Death Penalty: Assessing the Danger of Mistaken Execution, issued on October 21, 1993, and became DPIC’s first Innocence List.

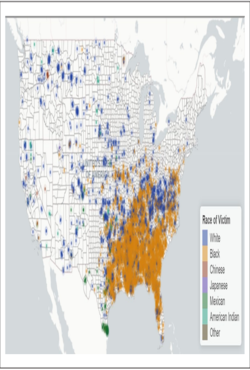

Since states began reenacting capital punishment statutes in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 1972 decision in Furman v. Georgia striking down existing death penalty laws, at least 185 people who were wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death have been exonerated. These wrongful capital convictions have happened in 29 different states and in 118 different counties, showing that, in whatever part of the country they are tried, capital defendants face an inherent risk of wrongful conviction. Florida has had the most death-row exonerations of any state, with 30 since 1973, followed by Illinois with 21, and Texas with 16. Cook County, Illinois leads all counties with the most death-row exonerations (15) since 1973, followed by Cuyahoga County, Ohio; and Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, with six exonerations each. Maricopa County, Arizona; and Oklahoma County, Oklahoma had five each. Those five counties, each with a history of police and prosecutorial misconduct and of being outliers in their excessive pursuit of the death penalty, account by themselves for a fifth (20%) of the nation’s death-row exonerations. And more than 95 percent of wrongful capital convictions and death sentences from those counties involved some combination of police or prosecutorial misconduct and witness perjury or false accusation. Twenty-six counties have more than one death-row exoneration, collectively accounting for 50.3% of all of the wrongful capital convictions that have resulted in exonerations

Washington, DC: Death Penalty Information Center, 2021. 31p.