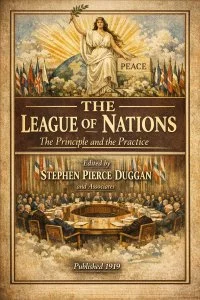

By RAYMOND G. GETTELL (Author), Colin Heston (Introduction)

First published in 1924, this book emerged at a time when the study of politics was being transformed from a largely historical and moralistic pursuit into a more rigorous, analytical discipline within American universities. Gettell’s work bridged the gap between the classical humanistic tradition of political reflection and the emerging political science of the early twentieth century, providing a lucid narrative of the major thinkers, schools, and debates that shaped Western political ideology.

The early decades of the twentieth century saw increasing professionalization in the social sciences, especially in fields like economics, sociology, and political science. Within political science, there was a tension between the empirical study of institutions and behavior (what would later be called "positivist" approaches) and the normative-historical approach that emphasized values, ideologies, and the moral purposes of politics. Gettell’s work traces the development of political ideas chronologically, beginning with the classical thinkers of ancient Greece—particularly Plato and Aristotle—whose inquiries into justice, the ideal state, and the nature of citizenship set the stage for centuries of political reflection. He then moves through the Roman period, early Christian thought, medieval scholasticism, Renaissance humanism, the rise of early modern political theory (with Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau), and onward to the nineteenth century, examining liberalism, socialism, nationalism, and other emergent ideologies.

For the modern reader, returning to Gettell’s work can serve as both a foundation and a springboard—a foundation for understanding the grand narrative of Western political thought, and a springboard for questioning, expanding, and diversifying that narrative to include new voices, global perspectives, and contemporary concerns. In it is an invitation to reflect critically on the ideas that continue to shape our political world. In an era marked by resurgent nationalism, territorial conflict, and the weakening of multilateral institutions, History of Political Thought retains a sobering relevance. Across the globe, from Ukraine and Russia, to Israel and Palestine, to China and Taiwan, we witness conflicts fueled by competing historical narratives, divergent political ideologies, and the enduring potency of the concept of sovereignty. These disputes often invoke deeply rooted claims to land, culture, and legitimacy, echoing ideas that can be traced back to the very thinkers Gettell profiles—whether it is Hobbes' notion of authority and order, Rousseau's theories of collective will, or the romantic nationalism that pervaded 19th-century political philosophy.

The idea of a world governed by shared norms—what Kant envisioned as a “perpetual peace” based on republicanism and international cooperation—remains elusive. States remain the final arbiters of their own security, often dismissing international judgments when they conflict with national interest or identity. Gettell’s text unintentionally underscores the fragility of systems that depend on consensus and voluntary compliance. Just as no political theory he surveys offers a perfect formula for reconciling liberty with order or equality with authority, no international institution can entirely overcome the foundational dilemma of political life: how to balance the need for collective restraint with the desire for self-rule. The UN, lacking coercive power over its most powerful members and constrained by veto politics in the Security Council, reflects this unresolved tension.

As global politics once again teeter between cooperation and confrontation, Gettell’s work calls us back to the deeper philosophical questions that must underlie any lasting peace: What is legitimate authority? Who decides? And how can competing visions of justice coexist in a shared political space?

Read-Me.Org Inc. New York-Philadelphia-Australia. 2025. 433p.